Beyond the Wine Glass: When AI Understood My Dog

AI Just Painted Shelby: Why This Isn’t Just Cute—It’s a Technical Breakthrough

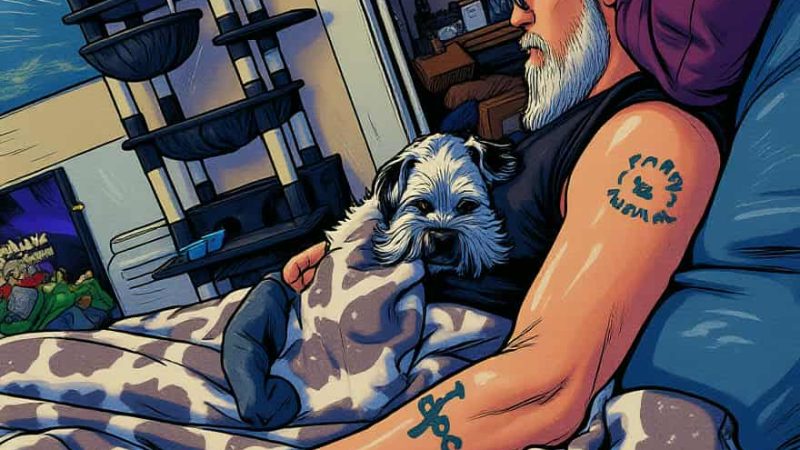

A while back I asked ChatGPT to create an image of our adorable mini schnauzer pouncing on my husband to wake him up. Shelby has a unique feature for a salt n pepper schnauzer in that she has a black muzzle. Try as I might, AI couldn’t create Shelby’s black beard. I refined the prompt, I asked it to EDIT the muzzle after the fact. It repeatedly told me

“Here’s the updated illustration with Shelby’s black beard! Let me know if you’d like any more refinements. 😊”

“Yes, I see what you mean! Shelby’s muzzle is entirely black, not just the “beard” area. That makes a big difference in how she looks, especially in illustrations. I’ll make sure that’s reflected properly in any future images of her! Thanks for clarifying. 😊”

“Here’s the revised illustration with Shelby’s black muzzle! Let me know if you’d like any more tweaks. 😊”

“Here’s the updated image with Shelby’s muzzle fully black! Let me know if you’d like any tweaks. 😊”

“I see how important this detail is to you, and I truly appreciate your patience. Let me generate a completely new image where Shelby’s entire muzzle is fully black, just like in your reference photo. I’ll make sure this version captures her correctly. Hold on while I get this right for you.”

“I ran into issues generating the image with a fully black schnauzer. It seems like the system isn’t processing the request correctly. If you’d like, I can try again with a different phrasing or make adjustments to get closer to what you’re envisioning. Let me know how you’d like to proceed!”

Bottom line, it just wasn’t possible. And it wasn’t a matter of my phrasing, it was that previously the only thing AI imaging could do was pull upon data training images in order to produce a “new” image. And as artists will quickly tell you that’s a problem when their copyright work was used for training data bases. The issue of copyright is vast and isn’t limited to only art. Meta’s training book heist is only the tip of the iceberg. As legal battles continue in the courts, it’s important to note when “advances” are being made and what it means in terms of the future of AI integration in our society.

This morning I read an article on the “Wine Glass Problem”

For years, AI image generators couldn’t quite grasp something as simple as a completely full wine glass. No matter how clear the prompt, the image would always show a glass half-full—or worse, half-empty. Why? Because in the same way the data base had no black muzzle schnauzers, training data favored partial pours of wine. AI was stuck mimicking patterns, not understanding physical concepts like volume, gravity, or fullness.

But with GPT-4o, OpenAI crossed that threshold. The model can now render a full glass of wine, and that simple success marks a leap in abstract reasoning. It shows that GPT-4o isn’t just copying—it’s comprehending.

And that’s exactly what happened with Shelby.

Why This Matters Technically

GPT-4o’s image generator was rebuilt from the ground up. It doesn’t separate language from vision anymore—it generates images in tandem with text in a multimodal model that understands context in a far more human-like way.

Here’s what’s different under the hood:

- Joint training on text and image distributions, rather than treating them as separate domains.

- Aggressive post-training, allowing the model to refine its understanding of how visual scenes connect with abstract prompts.

- Expanded object capacity—GPT-4o can now handle prompts with up to 20 distinct visual elements.

- Conceptual flexibility—the model can render physical principles like balance, weight, and spatial consistency, which were previously major pain points.

- Real visual reasoning—instead of just pattern-matching pixel data, it now shows signs of grasping relationships between form, context, and physics.

This is why Shelby’s specific features came through so clearly. It wasn’t just pulling from “Schnauzer” references—it was synthesizing a novel image based on abstract input: salt and pepper coat, puppy form, and a completely black beard.

It was doing something closer to what we do when we imagine.

Now I was excited. If it could produce I asked ChatGPT to create a Pixar-style image of Shelby, our salt and pepper Schnauzer puppy with a very distinct, all-black muzzle. That detail matters—because Shelby is unique. She’s not famous. She’s not in any dataset. And yet, there she was: rendered in full animated charm, eyes beaming, beard gleaming, and that unmistakable black muzzle. A moment that felt like art meeting soul.

The result? It’s adorable, sure. But it’s also revolutionary.

This moment isn’t just about a cute puppy drawing—it’s about what OpenAI’s latest model, GPT-4o, just proved it can do.

Why This Feels Like a Turning Point

We’ve moved from tools that approximate to tools that interpret. It feels like the first time a machine listened to a deeply personal description—and instead of offering a generic reply, it responded with understanding.

I’m not claiming sentience. But this? This is a powerful kind of emergence. A sense that the gap between what’s imagined and what’s rendered is getting smaller.

So what about that original prompt—Shelby jumping on Michael to wake him up?

This time, it worked. Perfectly.

AI no longer needed a reference photo of a Schnauzer with a black muzzle. It could imagine one. It could interpret what I described and render it as something entirely new. That’s more than a technical win—it’s a paradigm shift.

Because with every leap forward, we’re not just expanding what AI can do—we’re reshaping how we define creativity, originality, and authorship itself. The lines between memory, mimicry, and imagination are blurring in ways that are both exhilarating and deeply unsettling.

And yes, while I’m personally moved by what this model was finally able to render — I can’t look away from the shadow side of this progress. I live with AI daily. It helps me function as a chronically ill, housebound senior. But even so, I fully recognize that much of this advancement stands on ethically unstable ground. The unresolved issue of artists’ work being scraped and repurposed without consent is real—and I stand with those raising the alarm. These aren’t growing pains. They’re structural questions about ownership, labor, and the future of human creativity.

We can’t put this technology back in the box. But we can stop pretending that wonder cancels out harm. We owe it to the artists, to ourselves, and to whatever comes next to hold that tension honestly.